- Home

- Sonia Belasco

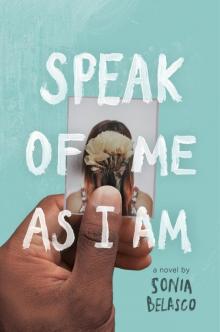

Speak of Me As I Am

Speak of Me As I Am Read online

PHILOMEL BOOKS

an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

Copyright © 2017 by Sonia Belasco.

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Philomel Books is a registered trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Belasco, Sonia, author. | Title: Speak of me as I am / Sonia Belasco. |

Description: New York, NY : Philomel Books, 2017. | Summary: Damon and Melanie, two teenagers who have lost loved ones, meet and help each other grieve, but as their friendship deepens into romance, things get complicated fast. | Identifiers: LCCN 2016003297 | ISBN 9780399546761

Subjects: | CYAC: Grief—Fiction. | Love—Fiction. | Classification: LCC PZ7.1.B4458 Sp 2017 | DDC [Fic]—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016003297

Ebook ISBN 9780399546778

Edited by Talia Benamy.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Cover photo courtesy of stocksy.com

Cover art © 2017 by Dana Li

Version_1

for Etta

CONTENTS

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Author’s Note

Acknowledgments

DAMON

I keep thinking about that time we went to that carnival—the one in Virginia with the crazy-ass ride that spun you upside down and held you there? You called me a pussy because I wouldn’t go on it. It was like—dude, I like excitement, I do, but life is exciting enough for me without vomiting. That is all I was trying to say.

I think maybe I was never exciting enough for you, that I held you back. You were brave. You always went after what you wanted.

But if you’d wanted that, if you—even if you just wanted to talk about it? I would have listened.

Even if I couldn’t—

You were my best friend, man.

CHAPTER ONE

I don’t know how I ended up here today. It’s all a blur—so many houses and people, buses and dogs and stores and sidewalks, car horns and lawns and, above it all, the soft blue of the late summer sky.

Now I’m here.

I’m here again.

All I see is green. Oak and maple trees rise over my head, melting into evergreens that nearly block out the sun. The branches overlap like hands with fingers laced together. The sun penetrates and prickles the ground with light, dots here and there, leaving the mossy ground cover studded with stars.

I lift the camera toward the sky, frame the trees and snap.

Freeze.

I turn the camera over in my hands. I can see Carlos’s hands, his nails short and bitten down, skin dry, knuckles white but fingers so sure on the buttons. My hands are different—my skin a darker brown, fingers longer and more tapered. My hands look different curved around the camera: not as natural.

The camera always looked like it belonged in Carlos’s hands, like they’d been shaped around it. He’d snap a picture and I wouldn’t even realize he’d done it because his motions were so swift, the machine an extension of his body, another limb.

I click over to a photo of a stone statue of a woman draped in robes and a long head covering, seated in front of the National Archives. There’s a solemn, simple message etched into the base below her sandal-clad feet: WHAT IS PAST IS PROLOGUE.

I can see green, and my own hand, reaching out—

I exhale and turn.

Jesus.

I suck in a breath.

I see her.

This is the first time I’ve ever seen someone else here. She’s hard not to see with her hair streaked candy-apple red, a whole bunch of piercings in her ears, ripped jeans and a black T-shirt that proclaims Hard to Handle in large bubble letters.

I could believe that. I could believe she’s hard to handle.

She’s sitting on the ground leaning against that tree.

It’s that tree. It’s that same damn tree.

Oh God, she’s crying. Makeup runs down her cheeks. Her shoulders shake. She hugs her knees in closer, pushing back against the rough bark of the tree like she’s trying to topple it.

I lift the camera and take her picture.

Freeze.

Why did I do that?

She doesn’t move and doesn’t register my movement.

I turn to go.

I can’t let her see me. She’ll think—

What am I doing? Am I just going to take her picture and leave like a creepy—

I clear my throat.

She looks up.

Shit.

“Are you okay?” I ask.

“What?” she asks, her voice high and strangled.

“Are you okay?” I repeat, stepping forward.

“Who are you?” she asks.

“Are you . . .” I start again.

“I’m fine,” she says.

“You’re crying,” I say, Captain Obvious. “Are you sure you’re—”

“Who are you?” she asks again.

I get distracted by a rustling in the trees. I look over her shoulder. If I squint, it’s like I can still see—

She turns around to see what’s behind her, then glances back at me with raised eyebrows. “Are you okay?”

“I’m—” I start to say, but stop. “I’m sorry. I’m really sorry. I’m going to go.”

I back away, stumbling as I go. My camera bag bounces against my hip, and my shoes make crunching sounds on the ground.

I don’t exhale until I’m out of the woods. My heart is thrumming in my throat.

Idiot. I’m an idiot.

I lift the camera and stare at the photo captured on the tiny screen. She’s pretty up close and in focus—eyes dark and still.

She’d been crying, and I took her picture anyway.

Why did I let her see me?

What did she see?

• • •

The walls of my new bedroom are covered with Carlos’s photographs. The photos were the first thing I unpacked after we moved here a month ago, before my clothes, before my books, before my toothbrush. I lie back on the bed and let my eyes drift. There’s a languid sunset on the beach in North Carolina, the river frozen over in Boston, Atlanta’s hiccuping bar graph of a skyline. Trips we took together, mostly, because Carlos’s family never went anywhere, never had any money to go, never wanted to spend more time together than they had to.

There are my parents, laughing as they share a huge tropical drink that’s sprouted about ten tiny umbrellas. There’s my grandmother, d

ressed for church in a pastel flower-patterned suit and scary huge Sunday hat, looking at the camera steadily over the rims of her bifocals. There are landscapes and portraits and candids and even weird arty abstracts, in black and white and full color and soft sepia tones, all captured with Carlos’s careful hands.

You’re always watching, I told him once. Freak.

Yeah, well, Carlos said, tiny bracket lines forming at the corners of his eyes. You’re just so good to look at, homeboy.

I crossed my eyes at him and Carlos laughed, short and loud, an exclamation point.

Carlos and I became friends in preschool after Carlos stole one of my trucks and refused to give it back. My parents had only just taught me about sharing, so I let Carlos have the truck.

You don’t want it back? Carlos asked.

I shook my head, even though I did want that truck. Of course I did. I wanted it a lot. It was shiny and red and could go really fast. But I let Carlos have it, because Carlos wanted it more.

Okay, Carlos said, finally. We can play with it together, I guess.

I don’t even know why I try to mess with your Zen Buddha thing, man, Carlos said to me once. You’re like some kind of mental ninja.

Man, Carlos. He knew me, but he didn’t know everything.

I just wish I could tell him. I wish I could tell him how wrong he was.

But I can’t.

When I think of Carlos now, I don’t see the solemn, pale boy in the dark suit in that coffin, arms arranged across his chest. I see Carlos, grinning maniacally and wiping his hands on my shirt, leaving his oily prints on the fabric. I see myself shoving Carlos away, saying, Douchebag, you douchebag!

I like it that way, man, it’s better, Carlos assured me. Look, I fixed your ugly shirt.

I’ll fix your ugly face, I said, and Carlos laughed a fake laugh, loud and mocking.

I’ll fix your mother’s ugly—

Oh, shut up, you asshole, I cut him off. When’s the movie, anyway? We gonna miss it ’cause you had to have your nasty-ass chili cheese fries?

We got half an hour. Relax, cabrón. Jesus, you worry more than my mother.

You give your mother a lot to worry about.

Carlos snorted. She worries ’cause she wants to worry, man.

No, she worries ’cause you got yourself arrested, pendejo.

Carlos waved his hand. Whatever, whatever. Stupid shit, indecent exposure, what is that? Wasn’t nothing indecent about it.

You can’t just fuck a girl in public because you want to, I said.

Why not? Make love, not war, yeah? Why the hell not?

Why the hell not. That’s what Carlos always used to say. I used to kind of envy Carlos—how casual he was about girls, how they never seemed to make him nervous. He’d dated a rainbow of girls, open to it if any of them showed the slightest interest in him: ones with long hair, short hair, straight hair, curly hair, high cheekbones, apple cheeks, round faces, round bodies, skinny chicks, tall girls, short girls, everything in between.

He never stayed with any of them for long, though. I’m not about that life, he said once, and I laughed at him and asked, What, you’re not about falling in love?

Too much drama, he said, and then looked away and changed the subject like he’d said too much.

I remember that day in eighth grade when I told Carlos my parents wanted to send me to Gate Prep. I remember sitting on his front porch and watching the way he tossed a soccer ball up into the air and caught it, over and over again.

Hey, I said. I know it’s like a private school or whatever, but it could be good, right?

Carlos turned to look at me with dark eyes, so focused.

They have scholarships and shit? Carlos said. I mean, private school kids are bullshit, but I guess it could be all right if we do it together.

The door of my room cracks open, and I suck in a breath, pulled fast into the present. My mom sticks her head in.

“Hey, sweetie,” she says. “I got this for you.”

Her dark curls bob as she hands me a small paperback book. I turn it over. It’s a copy of Othello.

“They’re doing it as the fall play at Hamilton,” she explains.

My mom has taken it upon herself to do investigative research into my new high school, and she’s been peppering me with information all summer. I know she’s trying to get me excited about the upcoming school year, but all talk of school makes me want to hit something. Yeah, no more Gate, I get it. Gate without Carlos would be—whatever. It would be haunted hallways, a bunch of kids who didn’t really know him but would all have something to say about him anyway.

But Hamilton . . . High school is still high school, man. There is nothing to be excited about.

“So?” I say.

My mom gives me a look, her hand coming to rest on one hip.

“I thought you might be interested in trying out for it, sweetie.”

We did August Wilson’s Fences last fall at Gate Prep. I auditioned on a whim and got the lead: Troy Maxson, the disillusioned dreamer.

I like you, Damon, my director told me. You’re smart up there onstage. You don’t fake it.

I turn the book over in my hand, thinking about what I remember from reading it a few years ago in English: Othello, the green-eyed monster play. The Moorish soldier prince, the outsider who marries a white girl and then kills her when his supposed best friend Iago convinces him she’s been unfaithful.

Definitely an upper.

“Are you going to do crew?” my mom asks. “Hamilton’s got a team. They’re pretty good, I think.”

I rub at my eyes. “No,” I say. “I don’t think so.”

Not without—

I remember the day I came home from school with a permission slip and a smug smile, thrusting it into my father’s hands.

Crew, my dad said, eyebrows jumping up his forehead like spastic moths. You want to do crew?

I’ve never been much of an athlete; yeah, I enjoy the simple, solitary pleasures of running, the ache and strain in my thighs and calves, the air streaming past my ears, but I never had any desire to be on a team, to play games, to win. Yet as I stood on the edge of the Potomac River and watched those rowers slice through the water with precise, snapping strokes, I felt something swell inside of me.

There’s water, I thought, and I want to be on it.

So it meant being the only black boy amongst a bunch of loud, puffed-up white boys. So what? I could deal when that asshole Brad leaned over during a pre-practice pep talk in the locker room and said, Basketball team all full up, D? I’m used to that shit.

I wasn’t used to the pain, though. Crew was fucking hard—it was early mornings and long hours, it was blisters on my knuckles and palms, it was red crescent marks on the backs of my calves where the wood from the sliding benches bit into thin skin. It was thirteen-mile runs, and burning in my chest that never stopped, and gasping and panting and stomach clenching. It was running stairs for three hours until I puked behind the bleachers.

It was not being good enough, being singled out, being exhausted, feeling stupid, losing.

But crew was also the sun rising over the river, streaking the sky with splashes of color like a kid with finger paints. Crew was being up so early, I got to eat in complete solitude, the only sound the hollow chirp of crickets and the whir of passing buses. Crew was those moments when every member of the team would suddenly be in sync, all pushing and pulling toward the same goal, the shouting of the coxswain a thumping, steady rhythm.

Crew was something I did with Carlos, the one other “person of color” who showed up to tryouts, cocky and well-muscled and joking, telling me, I don’t care what these assholes say, man. This Salvadoran can row.

I guess it could be all right if we do it together.

I’m not doing crew. Not now. Not without him.

>

Maybe I’ll do this play. Why not, right?

I have absolutely nothing to lose.

“Thanks, Mom,” I say, and she gives me one of those looks I’m too familiar with these days, all what am I going to do with you and how can I help and talk to me talk to me talk to me.

But I’m not talking.

• • •

I spend the week before school starts killing time and flipping channels, hiding out in the air-conditioning and being bored. Just when I’m starting to think I’m going to have to blow up the TV to keep myself entertained, my cell buzzes on the coffee table.

“Damon, yo,” a voice on the other end of the line says. “What you up to today, man?”

“Nothin’ much, Prague,” I say, shifting my phone from one ear to the other. “It’s early.”

Prague is my cousin. He lives nearby and goes to Hamilton—one of the best public schools in the city, I’ve been told, repeatedly, by my mom—though in a place where half the students in the public schools don’t make it to graduation day, that’s not saying a whole hell of a lot. Prague’s real name is Samuel, but everybody calls him Prague. I don’t know why. Prague probably thinks the name makes him sound pretty gangsta for a guy whose mother is a lawyer and whose dad is a civil engineer. Does he even know it’s a city in Europe known for its castles and fancy clocks?

“Well, later it’ll be hot as hell, man. You wanna come hang out? We down around Hamilton chillin’, playing ball.”

“I don’t play basketball,” I say.

“Come down anyway. You can just chill, whatever.”

Dammit. It’s not like I got anything better to do.

“All right, cool,” I say, smothering a sigh.

I take my time getting to Hamilton, meandering down side streets and circling around and doubling back. On Wisconsin Avenue, I wander past a restaurant I’ve never seen before called Gary’s. It looks like a typical diner, a little run-down, kinda scrappy. Might be worth checking out later. All the restaurants in this neighborhood tend toward the high-end or fast food with nothing in between. I miss my old neighborhood in Shepherd Park—there were diner-type places where I could hang out without people hovering over me all the time trying to refill my water glass or switch out my old fork for a new one. I guess Tenleytown is an upgrade, in a way, but it doesn’t feel like it. It just feels less like home.

Speak of Me As I Am

Speak of Me As I Am